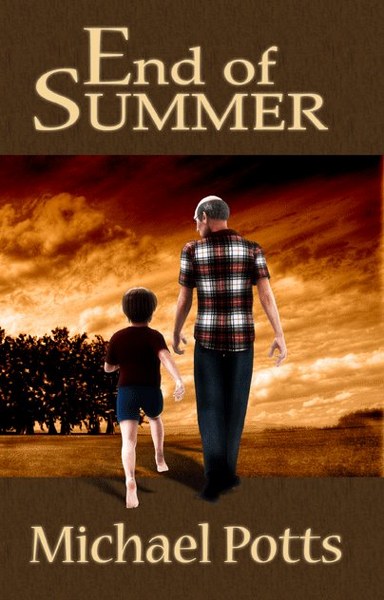

End of Summer by Michael Potts Book Tour and Giveaway :)

End

of Summer

by

Michael Potts

Genre:

Coming of Age

A

young boy. An old man. And a journey of the heart.

A

middle aged man, Jeffrey Conley, has obsessive interests, including a

fascination with death and the process of dying and a fetish for the

sound of a woman's heartbeat. His wife, Lisa, encourages him to get

help. His psychologist diagnoses him as having Asperger's Syndrome, a

mild condition on the Autism spectrum. When his granny dies, Jeffrey

returns to Tennessee for her funeral, and then walks the same field

he walked with his granddaddy as a child. On that cold, late November

day, Jeffrey walks toward The Thicket, an outcropping of trees and

vines from the woods adjoining the field that crossed the fence and

are invading the field. In that special place he and Granddaddy would

sit and talk as Jeffrey swung on vines or sipped cola. The middle

aged Jeffrey looks back to that time, to the summer of his ninth

year, an idyllic year and a terrible year, a year of joy, a year of

loss and grief. Will Jeffrey Conley be able to discover and

understand his struggles by this journey back into his past. While

remembering Sunday dinners with relatives, hunting rabbits with his

granddaddy, or visiting the town square, Jeffrey rediscovers pain and

the worst loss of his life. Will he be able to make sense of his

life, his past, his obsessions, his faith? Or will he sink into

despair, The Thicket becoming a place of pain rather than redemption?

That is the fundamental problem of the book.

I liked to hear Brother Noland’s sermons best when they focused on Bible heroes. I always enjoyed the stories of Old Testament heroes, especially the battles between the good prophet Elijah and Ahab, the wicked king of Israel. I would shiver at the story of Naboth’s vineyard. I did not know for sure what a vineyard was, but I saw it was something that the evil king desired. I imagined Ahab’s wicked wife, Jezebel, nagging Ahab, then whispering in his ear, “Don’t worry about that vineyard. Just let me take care of it.” I felt fear when Brother Noland spoke of Naboth’s arrest and of the liars hired by Jezebel to accuse him of cursing God and the king. In my mind I heard Naboth’s cries as he was murdered. I was glad when God sent the prophet to tell Ahab he would die and dogs would lick his blood. However, Ahab repented and God told Ahab that bad things would happen to his family - but only after he died. I always wondered if maybe God was too merciful to Ahab. This Sunday’s sermon was not to be about an Old Testament hero after all. Brother Noland began in a tone of voice that made me shiver. “If you died today, would you be ready to face God in eternity? One day, you will die - this is a certainty. Not one of us will leave life alive. When Judgment Day comes, will your name be written in the Lamb’s Book of Life so you can enter into heavenly glory? Or will your name be missing? What a terrible thing it would be to fail to hear your name when they read from the Book of Life! To face eternity without God, to be without hope, to be lost in hell forever!” I usually liked sermons about hell. I found them exciting - like horror movies. I wrapped my fingers around the edge of the pew as Brother Noland continued. “How long is eternity? It’s hard for our minds to follow. Imagine that the earth and sun are solid balls of steel. Imagine that an eagle flies constantly to and from the earth and sun. Each time it reaches the earth, it brushes a wing against the earth. Each time it reaches the sun, it does the same. Now the eagle’s feathers aren’t really hurt by all this, but they wear a little scratch of the steel away from the sun and earth every time! The time it would take for that eagle to wear away the earth and sun is nothing compared to eternity.” I listened - transfixed. Until now, my sense of time and space had been limited and circumscribed. About the longest time period I ever thought about had been summer vacation, and distance was either measured in tilled acres like Granddaddy’s field, or in the time it took to get to school in Gilead or else to ride to Randallsville. The geographical limit of my world was the Sears store in downtown Nashville. Going there was a voyage of adventure. I shivered in my seat, even though the seventy bodies in the building had made it warm despite the squeaky air conditioner. I felt constricted, as if I were smothering. The immensity of eternity was like a weight, the steel sun and earth crushing me. I felt my small size, my short life. The lives of others grew smaller, too, as did the things I thought were permanent: the house, the field, The Thicket, the earth itself. As these thoughts ran through my head like a rabbit, I tried to stop them. I focused on Brother Noland’s eyes. “Do you really want to spend eternity in hell, in a place prepared for the devil and his minions? Imagine the hottest heat you’ve felt on earth. Take a stove eye. Imagine you turn your stove on high, until the eye turns bright red. Then take one hand, hold the other hand with it against that stove eye. Feel the searing pain. Listen to your hand sizzle. Then turn it around to the other side, do the same. Repeat with the other hand. The agony you feel is a small pinprick compared to the pains of hell. The pain of your sizzling, swollen hand will stop one day. The pains of hell never end. Trillions of times hotter than the sun. Darkness all around. Demons taunting you. And eternal regret. You’ll know you could have followed God, could have been baptized, could have become a faithful Christian, could have gone to heaven to be with God forever. But now you can’t! Not now! You’re lost, lost, lost for eternity.” Brother Noland never raised his voice. He sounded like the calm of the sea. Yet I found that made the message more frightening. I held my hands over my eyes, which I shut as if squinting to avoid the light of the sun. That made things worse - I felt pulled into darkness and saw a demon face with thick, leering lips sneering at me, its razor claws coming to cut my face before throwing me into eternal flames. I opened my eyes, focused on the schoolhouse lights hanging from the ceiling. Their warm yellow light calmed me. I was just a boy and had not yet reached the age of accountability, the age at which you had to be baptized. Most people figured that was about the age of twelve. When you reached that age, if you died without being baptized, you’d go to hell. No exceptions. But I was nine and should be safe for a while. If I died, I would go to heaven because I did not fully understand right and wrong. At least that’s how Brother Martin had explained it in Sunday school class. I thought about Granddaddy. He was lucky. He waited until he was sixty-five to be baptized. He did not die first and go to hell. I was grateful that Sunday when I witnessed Brother Noland lower Granddaddy into the water, then raise him up, dripping wet, out of the baptistery. Granddaddy was safe unless he sinned again. Even then he could ask God for forgiveness. I hoped that he asked God for forgiveness whenever he was mean to Granny. I could not bear the thought of Granddaddy burning in hell. Brother Noland gave the invitation for sinners to come forth during the invitation song. “If there’s anyone here is not a Christian, you should believe with all your heart that Jesus is the Son of God, repent of your sins, and confess them before men. Then you should be baptized into Christ for the remission of sins, and you will be a new child of God. If there’s anyone who is a Christian who has fallen away, we invite you to come forward and confess your sins so we can pray for you. Whatever your need, won’t you come forward as we stand and sing?” We all stood, stretching our legs to the sound of opening song books. Brother Martin began singing the words, and I sang along. I loved the first verse about judgment - the second verse was about heaven:

There’s a bright day coming,

a bright day coming,

there’s a bright day coming by and by.

But its brightness will only be for them who love the Lord:

Are you ready for that day to come? It was the third verse that reminded me of the sermon’s end and made me want to scream. I almost did. Words struck with the force of fear itself. There’s a sad day coming, a sad day coming, there’s a sad day coming by and by, when the sinner shall hear his doom, “Depart, I know thee not; are you ready for that day to come? I was about to leave my seat to come forward, but I caught myself, recalling that I was only nine and not old enough to sin. Still, God’s all-seeing eye seemed to be everywhere. I wanted to hide, to play outside for a while so I could avoid God’s fiery glare. I felt as if God were waiting for me to sin before killing me. Then he could send me to hell. Maybe I would be one of the eternally damned. What about my mama and daddy? Did they curse God just before the other car hit them? If they cursed, they did not have time to pray for forgiveness. And if they did not have time to pray for forgiveness, God would not forgive them. Unless God forgave every one of their sins, they would go to hell. I remembered that Brother Noland said in another sermon that it was wrong to assume that God would forgive someone in an accident who didn’t have time to pray. I read most of the Bible and knew what God did to sinners. God told the Children of Israel to stone a man to death who picked up rocks on the Sabbath Day. I figured that was kind of unfair. Not only would the man suffer when the rocks hit him; but, when he died he would go to hell. Later, in the New Testament, Ananias and Sapphira had lied to God about the amount of money they gave the church, and God had killed them both. I figured they went to hell too. It seemed so easy to get to hell and so hard to get into heaven. Didn’t Jesus say that the way was narrow? What if Granddaddy died and went to hell? What would I do? I thought about that, and figured that if I saw Granddaddy falling into hell on Judgment Day I would do something bad right then and there and go to hell myself. I would not want to be in heaven for eternity without Granddaddy. Then I was scared God would be angry at me for thinking such a thought, and I wanted to go home and hide under the covers. I felt better after the invitation song. No one had come forward today. Most of the time, nobody did. It was time for the Lord’s Supper. That, at least, was a break. Several men from the congregation assembled in the back of the church, then walked to the front. They stood behind a long wood table loaded with metal trays. Some trays contained what I had always thought were Saltine crackers, although people called them “unleavened bread.” The men would then distribute the trays row by row to the congregation. Church members would break off a piece of cracker and eat it. I did not understand what they were doing or why I was not permitted to partake. Only those who were baptized could eat the crackers. I figured that was good in a way, since my mouth was already dry. The men returned to the front, replaced the small trays, and distributed the big trays filled with tiny cups of grape juice. A man would pray for “this cup, the fruit of the vine, which represents Christ’s shed blood. May we partake of it in a manner well-pleasing in Thy sight.” I wanted to take one of those cups and drink, but I knew I would be in bad trouble if I did. After that, the men took two bamboo baskets and passed them out. Aunt Jenny gave me a quarter to put in the basket. I would hold the quarter flat in front of my eyes, where it would shine like polished silver. I liked the “clink” it made when it fell into the basket full of dollar bills and change. I calculated how many tiny tootsie rolls a quarter would buy. Then I thought about Sunday dinner. My stomach growled. It was finally time for the closing prayer. After the prayer, I quickly moved outside to shake Brother Noland’s hand. I didn’t have time to play with the other children on Sunday morning because the service ended after twelve noon, and Granny was not happy if the roast beef dinner in the oven burned. I walked to the car and waited for my family members. I got inside and sat in the back seat. I was glad Uncle Lawton had parked the car in the shade. It was hot enough in the car without the sun cooking it. When everyone else was finally in the car, Uncle Lawton put on the air conditioner, and once we were on the road, he lit a small cigar. In the enclosed space I felt as if I were about to choke, but I knew it was no use to ask Uncle Lawton to stop smoking. Aunt Jenny said, “Jeffrey, why don’t you crack your window just a little if that cigar smoke’s bothering you?” I did, and it helped some. We pulled into the gravel drive and parked under the Kiefer pear tree where a swarm of wasps had congregated to enjoy the fallen fruit. Stepping carefully to avoid the wasps, the whole family went inside as the screen door slammed shut.

Michael Potts has taught philosophy at Methodist University since 1994. A native of Smyrna, Tenn., he received a B.A. in Biblical languages from David Lipscomb University in 1983, a M.Th. from Harding School of Theology in 1987, a M.A. in religion from Vanderbilt University in 1987, and a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Georgia in 1992. He is the author of Aerobics for the Mind: Practical Exercises in Philosophy that Anybody Can Do(Tullahoma, TN: WordCrafts Press, 2014) and has co-edited an anthology, Beyond Brain Death: The Case Against Brain Based Criteria for Human Death, published by Kluwer Academic Publishers in 2000. He has twenty-five articles in refereed scholarly journals, nine book chapters, six encyclopedia articles, nine book reviews, and ten letters, including one published in the New England Journal of Medicine. He also has over fifty scholarly presentations, including an invited presentation at The Vatican in 2005. He has written three novels, End of Summer (2011), Unpardonable Sin (2014), and Obedience (2016), all published by WordCrafts Press. His poetry chapbook, From Field to Thicket, won the 2006 Mary Belle Campbell Poetry Book Award of the North Carolina Writers’ Network, and his creative nonfiction essay, “Haunted,” won the Rose Post Creative Nonfiction Contest the same year. He has also authored Hiding from the Reaper and Other Horror Poems. He enjoys reading, creative writing, vegetable gardening, and canning. Potts, his wife, Karen, and their eight cats live in Coats, N.C.

Michael

Potts

A history of literature from the late Victorian period up to the present reveals a number of writers who focus on death in some of their major works. Of course the major nineteenth century work is Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886). It is the first novel to directly confront the notion of “my death” from a first-person perspective. Death anxiety grew during this time period due to a loss of religious faith in Europe. The hopeful ending of Tolstoy’s novel reflects his life as a convert to Christianity. Fyodor Dostoyevsky, a convert from atheism to the Russian Orthodox Church, also was concerned with death and found the solution to the problem of death in terms of the Christian doctrine of the general resurrection of all human beings at the end of time. Twentieth century writers also reflected a concern with death. Miguel de Unamuno, a Spanish writer, focused on his fear of death as annihilation in his book, Tragic Sense of Life (1913). Unamuno was a man who struggled with religious faith all his life, and in the end was an agnostic. He struggled to find meaning in the face of a death that might well mean the total end of the self. A splendid book by James Agee, A Death in the Family (1957), beautifully expresses the experience of a boy and his family concerning the sudden death of his father in an automobile accident. As a model of beautiful prose, this book has no equal, in my opinion. It is difficult for a writer to combine an economy of words with a combination of words that expresses lovely images, but Agee manages to succeed on both fronts. The book is not as much about death anxiety as it is about a family’s reaction to a death and a boy’s reaction to the loss of his father. Yet it shows how death haunts Agee to the point that he had to write a semi-autobiographical novel which is, in a sense, a tribute to his late father. A short story with a main character who has a horror of death is John Updike’s “Pigeon Feathers” (1961). A young boy fears that death may be annihilation and desperately seeks proof of the existence of God. He finds such proof in an unusual way. Ernest Becker’s nonfiction book, The Denial of Death (1974) focuses on death anxiety in a powerful way. His approach is psychodynamic; his writing is vivid, clear, and deeply disturbing. My first novel, End of Summer (2011) is a Southern fiction novel with the theme of a boy dealing with death. Like me, he is obsessed with death and fears that his religion may be false and death nothingness. I think such fears drive some people to write. It is certainly a major factor in my own decision to write fiction as well as my decision to become a philosopher. In the end, I am Christian, and my view of death optimistic due to the hope of eternal life. To the modern world, that is superstition. Despite my doubts, to me, it is truth and goodness and beauty—and comfort.

Follow

the tour HERE

for exclusive excerpts, guest posts and a giveaway!

Comments

Post a Comment