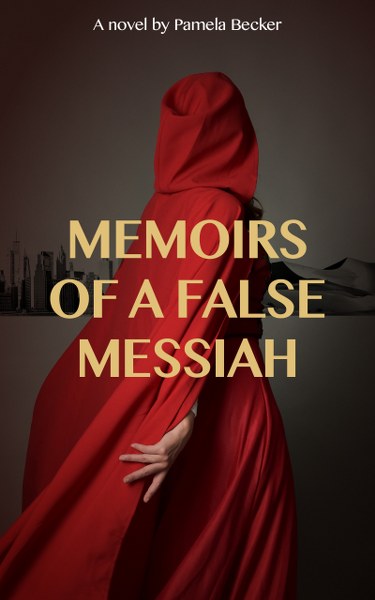

Memoirs of a False Messiah by Pamela Becker Book Tour and Giveaway :)

Memoirs

of a False Messiah

by

Pamela Becker

Genre:

Women's Fiction

MiMi

knows she is meant for something greater. She has a God-given

mission. This belief, together with tragedy, moves her from the

mixed-religion home of her early childhood to Orthodox Judaism in her

teens, to the establishment and development of her cult in the

Israeli desert. MiMi draws from the women in her life, in the Bible,

and in other ancient texts, weaving modern and biblical dilemmas, as

she shapes a truly unique place for her followers and herself. When

her life and utopian community grow more turbulent and even violent,

she questions her mission.

Deeply

affecting and thought-provoking, Memoirs of a False Messiah is the

richly told story of a woman's struggle to find her place in a world

reluctant to accept her.

Goodreads

* Amazon

Kindle Countdown Sale!

Sep 3 & 4 - only . 99 cents!

Sep 5 & 6 - only $1.99!

Sep 7 & 8 - reduced to $2.99

I

had my first vision at three.

One

night, as I slept, I saw myself as a grown woman, surrounded by lions

standing on hind legs growling at me, a wall of fire glowering behind

me. The only way out was a rope that descended from above but was

attached to nothing. I climbed it; my thighs rubbed raw from its

roughness, my feet bloody where the lions nicked them with their

teeth, my robes flaming, making me unbearably hot until I dropped the

garments below and continued climbing higher. “MiMi,

it’s okay,” my father’s voice broke through the dream, and I

opened my eyes. He sat on the edge of my bed and patted the damp

bangs away from my forehead. His thick black hair was messy, and he

wore only an undershirt and boxer shorts. His eyes, blue with specks

of gold, momentarily disappeared in the shadows of his

face and I could feel him shivering in my small room. To

my father - I told him what happened, watching his eyebrows join with

concern - this was a bad dream brought on by an overactive

imagination and normal childhood fears. But to me, the dream

signified much more. The next day, after I found scratch marks on the

bottoms of my feet, I asked my father to write down the details of my

dream as I explained them to him. I put that piece of paper in a

special paper-mâché jewelry box I was given on my birthday. I

had recently learned to read from a record of songs

based on Bible stories. I can’t imagine who might have given me

such an album. My father was a fallen Orthodox Jew, disowned by his

family when he married my non-Jewish mother. I’m surprised that not

only was the record ever brought into my parents’ home but that it

remained. With

a babysitter's help, I mastered the kiddie record player. I played

the Bible song record, and sitting on my knees in my bedroom,

followed the lyrics printed in large letters on the back of the album

cover. The

first song was about Daniel and the Lions’ Den. I don’t recall

how the words go anymore but the drawing on the album cover of a

small boy standing alone, surrounded by angry, vicious lions,

frightened me. I would close my eyes as I listened to the song and

imagined myself in the den. After

the night I had my vision, my parents paid more careful attention to

my education. The Bible record disappeared and was replaced with one

of fairy tales, of helpless beautiful girls saved at the last minute

by their handsome princes. I commented that the princesses’ parents

didn’t take good care of them, and soon that record disappeared

too. My father took to setting me on his lap, and we read the

newspaper together. In the family room, the television off and all my

toys put away for the evening, I would sound out the headlines, and

he would read me the articles. That’s

one of the happiest memories of my childhood, reading the paper with

my father, stumbling over words like "inflation," sitting

on his lap, my bright orange cotton-covered legs over his heavy blue

jeans. I remember staring at his toenails, which were always a little

too long and thick and thinking how powerful my father was. And how

safe I was sitting on his lap. That’s one of the nasty tricks of

childhood: the illusion of security. I

don’t have those kinds of memories about my mother. She worried

about my eating the right foods and growing at the correct rate. Born

small and underweight, like a raisin under a gray blanket in my black

and white baby photos, I looked sunken until I hit puberty, no matter

what she fed me or in what quantity. My mother, though, never looked

sunken, even in her worst moods. Her skin always looked tan, her

features sharp and her gray eyes clear. Her thin frame managed enough

curves to keep her from appearing too skinny. She

decorated my bedroom with yellow wood furniture and carpeting that

turned brown by the doorway. The wallpaper was striped yellow and

green. No flowers. No pink. A gender-neutral haven for me in my

formative years. Her own room was decorated with hefty wood, dark

wool afghans, and a shaggy brown rug. Nothing too feminine. That's

how she dressed, too. Her clothes in muted colors looked serious. Her

high, defined cheekbones and sturdy chin seemed to cooperate in

denying any femininity. She had no time for makeup or time-consuming

hairstyles, but I could tell by the way strangers looked at her that

she was an attractive woman. My

mother had movement. People stared at the way she walked or lifted an

object or how the wind blew her blond hair across her face. When she

carried her coffee mug to

her thin lips, you couldn’t help but watch the mug’s path, the

curl of her fingers around the handle, the purse of her lips as she

blew inside to cool the hot brown stuff. She was beautiful when she

was in motion. But

when she was still, her hair settled on her neck, her gray eyes

darkened, and her hands looked bony and long. She described herself

as very Shiksa-looking,

which I thought was my religion until years later I asked the

librarian for a book on Shiksa-ism

and

she set me straight. My

dad, on the other hand, was all dark - hair, eyebrows

and the stubble on his face that emerged by lunchtime. In a picture

of a trip to the beach that sat in a wooden frame on the bookshelf,

the black curls on his legs, arms, and even hands contrasted sharply

against the light down on my mother and me. I

had a friend Tracey who lived across the street. My mother and I

would go over there together. While the grown-ups drank coffee and

ate cake, Tracey and I played with girlie toys that I usually had no

access to at home: Barbies with all the accessories; dolls that wet

their pants or regrew their hair after haircuts; and jewelry making

kits that produced clunky pink bracelets and rings. I knew I was

supposed to look down on such gender-specific toys, which made

playing with them that much more fun. Besides, Tracey did anything I

told her to. I controlled our games. Tracey’s

mom, Chrissy, would get down on her knees and show us how to mix and

match Barbie’s clothes, and then she’d grab Tracey and rub her

tummy until she laughed. When she tickled me too, I would giggle

while my mom remained in her chair, her hot coffee still in her hand,

looking down at us smiling. Then she would ask Tracey to show me her

books. By

the time I started nursery school, I could read the Golden Book

series to the other kids. I remember having confidence way back then

of my power over my peers. They sat around me in a semi-circle and

listened quietly as I read, their eyes on me, not the pictures.

The teachers told my parents that I showed promise and moved me to

pre-kindergarten. My

father taught me numbers, and soon I was adding. My mother would put

me in the cart when she went grocery shopping, and by the time I was

five, I would add the prices for her. Of course, I made mistakes, and

remember crying because the decimal point that came between the

dollar and the cents sides baffled me. When

I went to kindergarten, my mother went back to work full-time. She

started to complain to my father that he had to help around the house

more. They spent Sundays doing laundry, cleaning the house and having

grown-up time, while I

played at Tracey’s. At her Catholic school, she could only wear

blue, gray or white clothes, and so we played dress up in the most

outlandish outfits. Chrissy would find us, trapped on the high

bathtub rim from where we had tried to see ourselves in the mirror.

She would peel off the layers of the odd clothes, leaving us in

Tracey’s ballet uniforms that we wore during these games, and sit

us down at the kitchen table with milk, cookies, paper and a box of

144 crayons that astounded me by its opportunities. Tracey

drew pictures of us in our outfits, the heads, hands, and feet always

too big. I sketched tall women with blond hair falling from the sky

into the mouths of flames. With over twenty shades of orange and red

to work with, I tried to perfect the fire each time. My mother

refused to tape the pictures on the refrigerator, so I kept

them in a pile in my desk drawer. Sometimes,

I stood in the kitchen doorway watching my mother and my dad make

dinner. My mother would cry as my father held her against his chest

for what seemed like a long time, or until something on the stove

started smoking. They were about

the same height, about 5’9”, and she stooped a little when he

cradled her head in his neck, her arms around his shoulders, his

hands gripping each other at the small of her back. I could see my

father’s face through strands of my mom’s blond hair, the shadow

of a beard showing, his teeth biting his lower lip and his eyes

focused on me. I hated that look of helplessness on my father’s

face and my mother’s weakness for causing it. No

one knew for sure what made her so sad as if it was some outside,

uncontrollable, indiscernible force. The years passed, and as I grew

bigger, my mother cried more and more frequently. She started missing

dinner once and then twice a week for mysterious appointments. She

would come home after I was already in my room for the night, and I

heard the pouring of coffee and my parents’ low voices in the

kitchen until I fell asleep. On those nights my father and I ate

simple dinners of spaghetti and salad. He’d ask me questions about

school and draw diagrams and word problems to show why subtraction

was important, and what ancient history has to do with today. I loved

those evenings so much; I secretly hoped my mother would have

her appointments every night.

Memoirs

of a False Messiah is Pamela Becker's debut novel. Originally from

New York, she has enjoyed a long career as a marketing executive and

consultant for some of Israel's leading technology companies. After

she was widowed with three small children, Pamela co-founded and

remains the active chairperson of the Israeli charity Jeremy's

Circle, which supports children coping with cancer treatment or

cancer loss in their immediate families. A graduate of the Writing

Seminars program at the Johns Hopkins University and the Arad Arts

Project artist residency program in Israel, she earned an MBA from

Tel Aviv University. Pamela lives with her husband and their five

children in Tel Aviv.

Follow

the tour HERE

for exclusive excerpts, guest posts and a giveaway!

Comments

Post a Comment